Misja Pec

For my third birthday, all I wanted was a chocolate cake. My mom promised me one, so I was excited for this grand delivery of layer upon layer of creamy chocolate covered in ribbons of icing. My whole family would be there with presents and kisses, singing “Happy Birthday” amid the streamers and balloons filling the air. I would finally feel like the princess I was destined to be. When the big day came, my mom plopped down a brown loaf with three tiny candles in front of me with a thud. There was no multi-tiered chocolate cake with towers of icing; there were no balloons, no streamers, no piles of gifts, and no one else in my family except my parents. In my three-year-old mind, everything was ruined.

Flash-forward 33 years later, and I’m sitting in my van with tears running down my face while I ice my ankle and lament my situation: It’s two days before my husband, Ben, and I are supposed to leave for a five-week climbing trip to Slovenia. My feet were about six feet off the ground on Change of Heart, a V6 in Bishop’s Buttermilks, when I jumped down and landed perfectly on the pads in a crouched position. A split second later, I lost my balance and tipped forward, my left foot twisting ever so slightly in an awkward direction. I felt a pop on the inside of my ankle and immediately grabbed it in pain. I quickly tried to walk it off only to realize that something was definitely wrong. Shock set in slowly, then mourning, denial, and grave disappointment, a similar process the mind goes through when someone dies. This was happening almost two years to the day after I broke my ankle (also bouldering in the Buttermilks) when my foot struck the ground between the pads, an injury that took me nearly three months to recover from.

To add insult to injury (pun fully intended), this round of ankle problems happened when I wasn’t even supposed to be climbing hard. I was in taper mode following a life-consuming, 6-hours-a-day training regimen. For the past two months, Ben and I had been visiting family in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and training at the local gym. Every Monday through Thursday we devoted ourselves to training like it was our job. Wake up, yoga, breakfast, then head to the gym for cardio, weightlifting, climbing, hundreds of pull-ups, campusing, hangboarding, Frenchies, circuits, TRX, leg exercises, 4×4’s—and that’s all in a single session. We were sacrificing prime Southern conditions at the half-dozen world-class crags near Chattanooga to toil away inside. I had even trained through a nasty weeklong flu that had me otherwise bedridden with soup and hot tea.

Training for power

Our goal to dispatch projects quickly on fantastic Slovenian limestone seemed like it was slipping away. My ankle turned into a large purple onion while my mind filled with doubt. What if it’s broken? Will I be able to push off the notoriously glassy feet of Misja Pec? What would I do with my strongest body ever and a bum ankle? Should I stay in Bishop in our van, just limping along and waiting? Waiting for what exactly, I wasn’t sure.

Two days later I was being escorted via wheelchair through three different airports (surprisingly the smoothest travel experience of my life), and we were on our way. I was nervous for what lay ahead. I wanted to be supportive of Ben because he had put in just as much training effort and was looking really strong, but I was feeling sorry for myself. We arrived to consistent rain, but the thatched-roof villages mixed with pastures of sheep and rolling hills covered in fog were overwhelmingly enchanting. I tried to do some physical therapy and keep busy with yoga, writing, movies, and cooking, but things were moving so slowly that after a week there I was disappointed in everything. I wanted to be climbing, but I could barely walk to the base of the wall.

All those weeks of training, the anticipation, the excitement; it had all been for nothing. I thought about the missed opportunities and the what if’s, digging myself a great dark hole of emptiness and gloom. I crawled in that hole, piled all my grief on top, and sat there, alone. I felt like a fool, like a child, like a brat. I felt like that 3-year-old who denied her mom’s homemade bread.

A chance meeting between Ben and a shoulder surgeon at the crag one day led me to Slovenia’s top physiotherapist, who happened to live right down the street. I was doubtful—what on earth would make him so great, but I would do anything to get out of this hell hole.

A rather large man examined my underwear-clad body while I walked around his office. Yanking on my inflamed ankle, he pressed and poked the most painful places with all of his might, telling me to focus on my breathing, always on my breathing. “Just breathe,” he said. “Look at your breathing, calm your breathing.” Then he sat down in a chair across from me and said, “Tell me, what is it that is causing you stress? I can see it in your eyes when you first came in. Something has you unsatisfied that is beyond this injury.” Taking a deep breath and deciding to trust him not just with my physical body but my emotional one as well I told him about the trials and tribulations of my marriage and the stresses I felt from it. He went on to say that as an athlete my whole being needed to be 100% focused on climbing, that any slight irritation, any emotional trouble, anything that could wobble me is harmful to my climbing and my health. With this kind of trouble a small injury can blow up into a big thing. Taking my hands in his, he told me I could climb as much as I want but warned me it would be painful. “Don’t worry, though,” he said, “because it is only the mind and the mind lives in the past.” As I walked out, he called after me, “Do not live in fear and enjoy your life.”

I walked out of his office a little bit looser both in my body and in my mind. He had helped to break up some of the stagnation in my ankle and he helped me to breath deeper, and to take responsibility for my feelings. I was being healed both physically and emotionally, something that you just don’t find with your typical doc in the States. Getting an ok from him also helped me to relax; his reassurance that it wasn’t broken, that it would heal were really all I needed. I was going to be ok, I just needed time, I just needed to let go of the preconceived ideas I had about performance and red-points and onsights. I just needed to relax and enjoy.

Taking it all in and waiting for the shade.

Expectations set you up for failure. If you do not achieve the one thing you desire, life can feel like a disaster, and it means you miss a larger piece of the puzzle: the greatness of the unexpected. Expectations make you rigid and closed off to other opportunities. They force you to demand a lot of yourself, of others, and of the universe at large. My expectations for this climbing trip, for all the glorious routes I would climb and prove my fitness to kept me blind to the path I was actually on.

I’ve always heard the saying “there is no success like failure,” and I’ve come to understand that it is in failure that we see ourselves for who we really are and what we’re made of. If I hadn’t hurt my ankle, I never would have gone to see the Slovenian physiotherapist Alan Lilic, I never would have come to understand myself that much more, and I never would have gotten a grasp on the things in my relationship that needed to be ironed out. I learned the difference between having a goal and having an expectation. Goals are things that I strive for, work for, and build myself for and it has always been that with enough preparation and enough will power to keep pushing through the ups and downs they can be met. My expectation was thinking that the goal would be met with ease, that just because I had trained I was guaranteed great victory in my climbing, that I was untouchable by obstacle. Having goals is great—it drives, motivates, and pushes you, but by expecting to always meet or exceed my goals, I’ve set myself up to be unhappy. When our expectations aren’t met, we’re left with a sort of self-imposed suffering called disappointment, and life is too short and too precious for such frivolity. My Technicolor foot barely fits into my climbing shoe now, and the pain of pulling on polished feet is subsiding more and more, but my climbing goals are still there, as well as my relationship that requires care and nurturing. For years I demanded that my mom admit she made a loaf of bread instead of a cake. Eventually she confessed it was a chocolate spice bread. We laughed over the silliness of it all, and she said, “That was probably the best bread I’ve ever made, which is too bad for you because I lost the recipe.” It’s unfortunate for me that I never tasted it, but unlike the fleetingness of a homemade pastry, climbing and life continue to offer up opportunities for new experiences, new goals, new processes and endless lessons. I’m fortunate beyond belief with the opportunities and accomplishments in my life. Some things have come with ease and some things have been a battle, leaving me bruised and scarred and questioning how bad I want it but I keep getting up and going back.

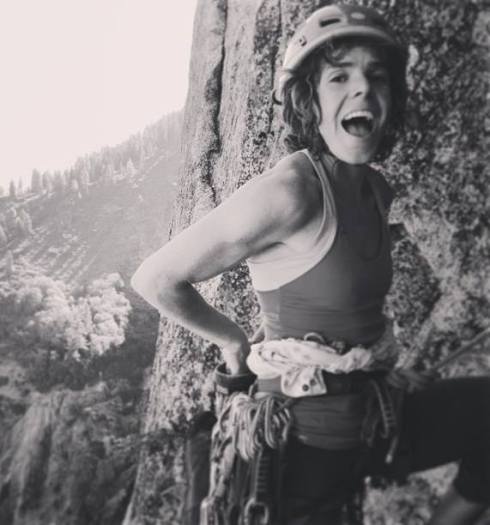

That sweet taste of sending a beautiful route. Pticja Perspektiva (8a+/13c)

all photos by http://www.bendittophoto.com

a version of this story was published in the May 2016 edition of Climbing Magazine.